5.5 Managing Contract Issues And Disputes

How a Contract Administrator manages contract issues and disputes is often based on how effective it was in including the appropriate clauses and processes into the contract to address issues and manage disputes when they arise in the execution of the contract. The following sections discuss the types of contract issues that may arise and how a Contract Administrator should use the contract terms and conditions to manage those issues if and when they occur.

There are many times where a public organization finds itself with the responsibility of managing a complex multi-million dollar program without adequate resources. An answer to inadequate resources is outsourcing, i.e., bringing on a contractor with the subject matter expertise to assist in managing the program for success. There are obvious benefits and challenges to this practice; the benefits being additional expertise where there is none; the challenge is that you now have one contractor managing another.

It is important to recognize that the government/state/city organization has fundamental inherent government functions that cannot be delegated to a contractor. If these inherent functions are delegated, it implies the contractor is now acting as an employee of the government (a personal service).

When it relates to procurement, the only people who should be making final decisions on how to spend taxpayer’s money are those authorized, delegated public procurement officials.

Federal Procurement Law defines inherent functions to be performed only by government employees. The SPO recommends this guidance as a good procurement policy and a preventative measure for procurement violations.

The SPO considers the following responsibilities inherently governmental:

- Determining what supplies or services are to be acquired by the Government;

- Approving any solicitation documents, to include documents defining requirements, specifications, incentives, and evaluation criteria;

- Negotiating cost and pricing;

- Awarding contracts;

- Approving post-award contract changes to include, but not limited to, ordering changes in contract scope, schedule, budget, taking action based on evaluations of contractor performance, and accepting or rejecting contractor products or services; and

- Terminating contracts.

Ultimately, it is the government’s responsibility to manage the contracts it procures, to make all final decisions on what they want and how much they will pay for it, with the ever-present goal in mind of achieving a successful outcome whilst safeguarding taxpayer’s money.

5.5.1 Extensions to the Period of Performance

The contract period of performance is usually a very firm date wherein performance or delivery must be completed. In certain circumstances an extension to period of performance may be warranted. Please refer to the change order and modification clauses in the contract for guidance on allowability, contractor deadlines to submit requests, and the process to issue the change to ensure it is legally enforceable. These clauses will also provide you tools if the request for an extension is unwarranted and will not be granted. When creating these clauses it is best to refer to HAR §3-122-3 for Extension of time on contracts and HAR 3-125 Modifications and terminations of contracts for guidance.

5.5.2 Price Adjustments

HAR 3-125 also provides clauses dealing with price adjustments to contracts. The clauses contained in the contract are very protective of the government’s interests and, if enforced, can keep a project on time and on budget. As stated above, the need to increase the price of a contract should be a rare occurrence. Ensure you are familiar with the contract clauses governing price adjustments to protect the project from unwarranted or frivolous claims. When warranted, the clauses will provide the appropriate procedure and different methods allowed to be used in pricing the adjustment.

5.5.3 Issue Tracking and Escalation

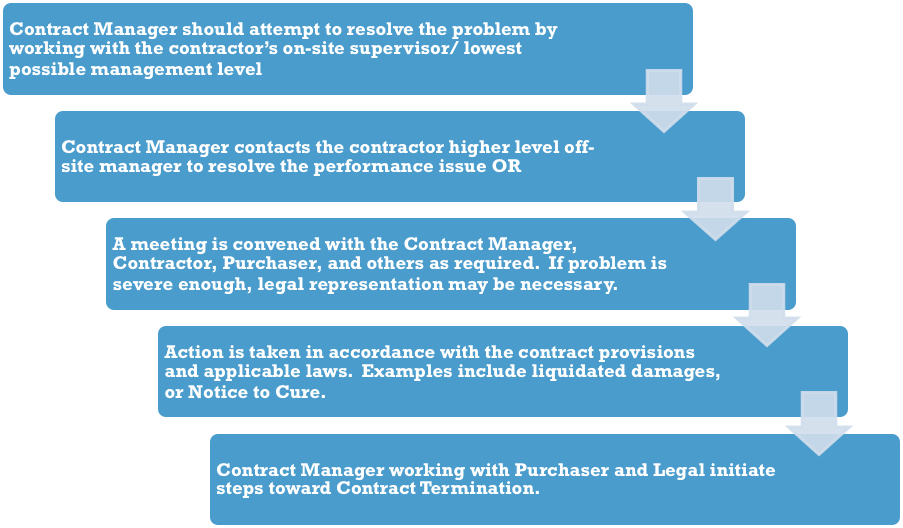

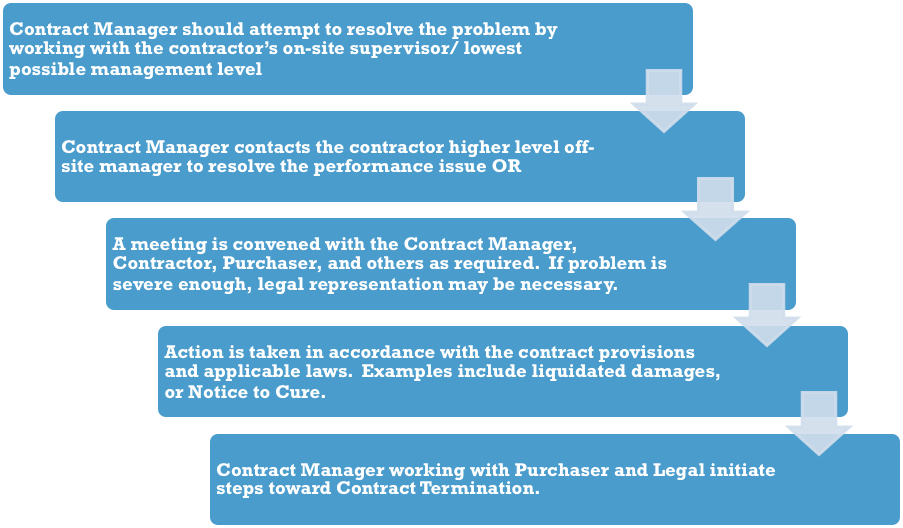

When issues arise in a contract, a Contract Administrator must act to address them. Some issues are simple and can be dealt with directly by the Contract Administrator. Other issues may be more complicated and require that the issue be escalated. Some issues that may arise during contract performance are characterized by disagreement leading to disputes between the contracted parties.

The key to effectively managing issues is establishing a clear issues tracking and escalation process, understanding the triggers that drive issue escalation and knowing what mechanism are available to effectively deal with issues as they progress through the issue escalation process.

The following figure provides a basic issues escalation framework that can apply to most any contract. ((For the purposes of this section a Contract Manager and a Contract Administrator have the same meaning.))

The primary goal of the issue escalation process is not to be punitive and/or penalize the vendor when an issue arises. Rather, it is meant to get the project performance back on track to effectively deliver the goods or services in the contract, while maintaining a positive vendor relationship.

If issues remain unsolved, the Contract Manager working with Purchaser and Legal should initiate steps toward Contract Termination as described in section 5.5.6 below.

5.5.4 Contract Disputes

Some issues that arise during contract performance are difficult to resolve. A dispute is a disagreement that is not resolvable between the parties to the contract. In accordance with HAR §3-126-25, it is the policy of the State to try to resolve all controversies by mutual agreement without litigation.

Formal legal action is always an option, however, there are many reasons both parties may be hesitant about pursuing formal proceedings. Formal legal proceedings can be expensive, lengthy, there is uncertainty of outcome, and it can damage the business relationship.

When parties cannot resolve disagreement about the meaning of the terms of an agreement a contractor may submit a claim in the manner set forth in the contract or in accordance with HAR §3-126-31. If the contractor submits as request for final decision to the Procurement Officer((Note in accordance with HAR §3-126-27 settlement or resolution of claims exceeding $50,000 shall be approved by the Head of the Purchasing Agency.)) then time-sensitive, procedural requirements apply to both parties that must be followed.

Contract Administrators should become familiar with the powerful provisions in the disputes clause. Agencies are strongly urged to engage their Deputy Attorney General or Corporation Counsel when a formal claim is received.

5.5.5 Right to Audit Vendor Records

Another method of addressing issues and/or disputes that arise during contract performance is to perform an audit in accordance with HRS §103D-317, which allows the purchasing agency the right to audit the books and records of a contractor or subcontractor under contract.

5.5.6 Contract Termination

It may sometimes be necessary to end a contract before the contractual period of performance has ended. The premature ending of a contract is referred to as “termination” and generally takes on one of the following forms:

- Termination for Convenience

- Termination for Default

Termination should begin only after sufficient consideration and consultation, as the consequences for both parties are extreme, and may require future litigation.

5.5.6.1 Termination for Convenience

Termination for convenience is one of the most powerful provisions in any public contract. A termination for convenience clause gives the State the unilateral right to terminate all or part of the contract when it is in the best interests of the State. The need to terminate a contract may arise for many reasons but generally occurs from changes in government priorities, funding, or other unanticipated events.

The process to be followed when terminating a contract depends on the nature of the contract. Procedures for termination for convenience of contracts for goods and services are found in HAR §3-125-21. Procedures for construction contracts are found in HAR §3-125-22.

For Executive Branch:

The Department of the Attorney General Conditions (form AG-008) contains language for termination and contract suspension that should be referenced for these matters. It is encouraged to attach this form to all solicitations.

5.5.6.2 Termination for Default

Termination for default, also referred to as Termination for Cause, is a standard term of any public contract allowing the State agency to terminate the contract in accordance with the contract provisions or HAR §3-125-17 for goods and services contracts and HAR §3-125-18 for construction contracts.

The HAR provisions cited above contain the basis for which a termination for default can be asserted as well as the very strict procedures that must be followed to ensure the termination for default is legally enforceable. Failure to follow these procedures in the manner they are proscribed places the State at great risk. Therefore, agencies are strongly encouraged to consult with their Deputy Attorney General or Corporation Counsel prior to proceeding with any termination action.

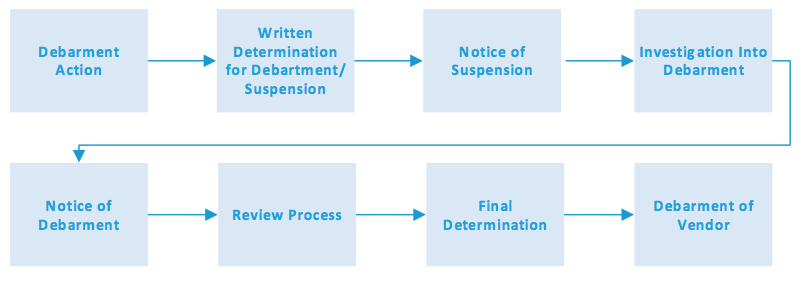

5.5.7 Suspension and Debarment

There are times when a contractor’s actions are so serious and compelling that it affects their responsibility as a contractor. As a result, the CPO may determine it is in the public interest or a governmental body’s protection to suspend or debar the contractor.

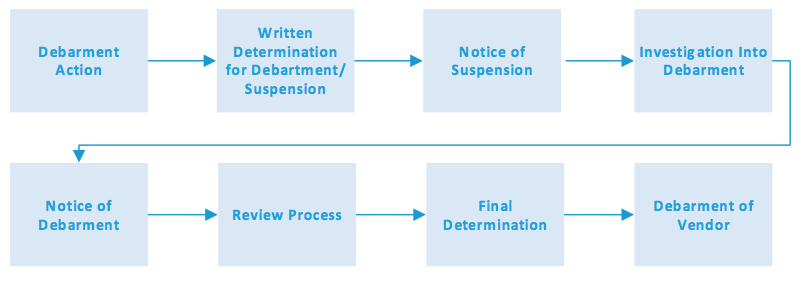

If there is probable cause to believe a vendor has acted in a way as to create cause for debarment, the CPO shall consult with the purchasing agency, attorney general (AG) and the vendor, where practicable, and draft a written determination. In general there are eight (8) steps to any debarment action:

5.5.7.1 Step 1: Debarment Action – HRS Section 103D-702(a)

Prior to commencing debarment action, the CPO must consult with:

- Purchasing agency;

- Attorney General (AG) or the corporation counsel; and

- Person or firm who is to be debarred (where practicable).

HRS Section 103D-702(b) sets forth the following causes for debarment or suspension:

- Conviction for commission of a criminal offense as an incident to obtaining or attempting to obtain a public or private contract or subcontract, of in the performance of the contract or subcontract;

- Conviction under state or federal statutes relating to the embezzlement, theft, forgery, bribery, falsification or destruction of records, receiving stolen property, or any other offense indicating a lack of business integrity or business honesty which currently, seriously, and directly affects responsibility as a contractor;

- Conviction under state or federal antitrust statutes arising out of the submission of bids or proposals;

- Violation of contract provisions, as set forth below, of a character that is regarded by the Chief Procurement Officer (CPO) to be so serious as to justify debarment action:

- Deliberate failure without good cause to perform in accordance with the specifications or within the time limit provided in the contract; or

- A recent record of failure to perform or of unsatisfactory performance in accordance with the terms of one or more contracts; provided that failure to perform or unsatisfactory performance caused by acts beyond the control of the contractor shall not be considered to be a basis for debarment.

- Any other cause the CPO determines to be so serious and compelling as to affect responsibility as a contractor, including debarment by another governmental entity for any cause listed in the rules of the policy board;

- Violation of the ethical standards set forth in HRS Chapter 84 and its implementing rules, or the charters and ordinances of the several counties and their implementing rules.

If the CPO determines the contractor’s actions are so serious and compelling as to affect the responsibility of the contractor, HRS Section 103D-702(c) provides that the CPO shall consider the following factors, however, contractor has the burden of demonstrating to the satisfaction of the CPO the contractor’s present responsibility and that debarment is not necessary:

- Whether the contractor had effective standards of conduct and internal control systems in place at the time of the activity constituting cause for debarment or had adopted those procedures prior to any government investigation of the activity cited as the cause for debarment;

- Whether the contractor brought the activity cited as the cause for debarment to the attention of the appropriate government agency in a timely manner;

- Whether the contractor fully investigated the circumstances surrounding the cause for debarment and made the result of the investigation available to the chief procurement officer;

- Whether the contractor cooperated fully with government agencies during the investigation and any court or administrative action;

- Whether the contractor has paid or has agreed to pay all criminal, civil, and administrative liability for improper activity, including any investigative or administrative costs incurred by the governmental body, and has made or has agreed to make full restitution;

- Whether the contractor has taken appropriate disciplinary action against the individuals responsible for the activity constituting the cause for debarment;

- Whether the contractor has implemented or agreed to implement remedial measure, including any identified by the governmental body or the chief procurement officer;

- Whether the contractor has instituted or agreed to institute new or revised review and control procedures and ethics training programs;

- Whether the contractor has had adequate time to eliminate the circumstances within the contractor’s organization that led to the cause foe debarment; and

- Whether the contractor’s management recognizes and understands the seriousness of the misconduct giving rise to the cause for debarment and has implemented program to prevent its recurrence.

5.5.7.2 Step 2: Written Determination for Debarment or Suspension

In order to debar HRS Section 103D-702(d) provides that the CPO shall prepare a written determination.

- CPO written determination shall:

- State the reasons for the debarment or suspension action; and

- Inform the debarred or suspended person of the rights for administrative review.

A copy of the written determination shall be included with the Notice of Suspension or Notice of Intent to Debar.

If cause for debarment exists, proceed to Step 5.

If probable cause for debarment exists, as detailed in the written determination, CPO shall issue a Notice of Suspension to the person or firm stating that:

- The suspension is for the period it takes to complete an investigation into possible debarment, but shall not exceed three (3) months, unless the CPO determines in writing that additional time is necessary to complete the investigation;

- Bids or proposals, if received from the suspended contractor will not be considered during the suspension period; and

- The contractor may request for a review (See Step 6). The written request must be received by the CPO within ten (10) working days after the person or firm receives the notice.

The suspension shall take effect upon issuance of the Notice of Suspension, and will remain in effect during any appeals, and may be terminated by the CPO, an administrative hearings officer, or by a court.

5.5.7.4 Step 4: Investigation into Debarment – HAR Section 3-126-12

Upon issuance of the Notice of Suspension, the CPO shall begin investigating cause for debarment and pursue debarment if cause for debarment exists. If results of the investigation show that cause for debarment does not exist, the CPO shall issue a final decision to the person or firm, and withdraw the suspension, after consulting with the AG or corporation counsel and the purchasing agency.

If cause for debarment exists, the CPO shall issue a Notice of Intent to Debar to the person or firm, by certified mail, return receipt requested, stating:

- A debarment is being considered;

- The reasons for the debarment action;

- The contractor may request for a review (See Step 6). The written request must be received by the CPO within ten (10) working days after the person or firm receives the notice; and

- The person or firm may be represented by counsel.

The notice of debarment shall also be sent to the AG and the affected purchasing agency(s).

- A review, when requested in writing by the person or firm proposed for debarment and received within ten (10) working days after receipt of the notice of the suspension or debarment action, shall be conducted by a CPO or designee (review officer).

- The Review officer shall send a written notice within fifteen (15) working days of the request for review, by certified mail, return receipt requested, and shall state the nature and purpose, the time and place of the review. Copies shall be sent to the AG or corporation counsel and the purchasing agency.

- If no request is received, a final determination may be made, after consulting with the AG or corporation counsel and the purchasing agency.

- In accordance with HAR Section 3-126-15, review shall be completed within sixty (60) days from the date set for the review. Weight to be attached to written evidence presented will be within the discretion of the review officer. The review officer may require additional written evidence to that offered by the parties.

- Review officer shall prepare a written determination recommending a course of action, and copies shall be sent to all affected parties, including the person or firm, the AG or corporation counsel, and the purchasing agency.

- The person or firm shall have ten (10) working days to file comments upon receiving the review officer’s determination. The CPO may request oral argument.

- After consulting with the AG or corporation counsel, and purchasing agency, the CPO shall issue a final determination to include:

- The right of the person or firm to commence an administrative proceeding under HAR 3-126 subchapter 5;

- Length of debarment, not to exceed three (3) years;

- Reasons for the debarment action; and

- To what extent affiliates are affected.

- Debarment shall be effective upon issuance and receipt of the final decision by the person or firm.

5.5.7.8 Step 8: List of Debarred and Suspended Persons – HAR Section 3-126-18

- A CPO making a suspension or debarment decision shall notify the State Procurement Office (SPO) of the action, including a copy of the decision to debar or suspend. The SPO shall issue an updated list of persons or firms debarred and suspended to all governmental bodies and post on website.

- Upon notification of a debarment or suspension action from the SPO, a CPO shall make a written determination whether to allow the debarred or suspended person or firm to continue performance on any contract awarded prior to the effective date of the debarment or suspension.

A list of debarred and suspended contractors is maintained by SPO and is posted to their website.

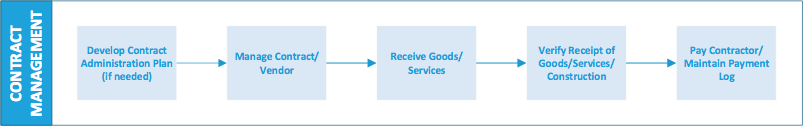

5.6 Receive Goods, Services or Construction

The purchasing agency is responsible for ensuring prompt receipt, inspection, and acceptance of all goods and services procured by the agency, unless otherwise specified in the contract. For each delivery, an agency must designate appropriate personnel to certify that the goods or services were received, that quantities were as stated, that the goods or services met specified requirements, and that condition was satisfactory or noted otherwise upon receipt.

5.7 Vendor Payment

Another critical function of contract administration is invoice approval and vendor payment.

To receive payment, vendors must submit invoices to the ordering entity with the required detail as outlined in the contract.

Invoices must be approved by the appropriate staff – review should include:

- Vendor is invoicing only for goods, services or construction received.

- Goods, services or construction have been received and accepted.

- Invoice is correct and complies with terms and conditions of contract.

- Total payments do not exceed the contract limits.

For further guidance on vendor payment and payment approval processes, refer to your agencies policies and procedures.